“It’s Not a Soft Option”: Rebuilding Reviewer Confidence in Qualitative Research

Qualitative studies are not second-class science. When designed and reported with rigor, they answer questions numbers alone cannot touch. So why do so many reviewers remain skeptical? And what concrete practices lift a qualitative manuscript from “interesting” to “fundable and publishable”?

The bias problem (and why it persists)

The bias problem (and why it persists)

Reviewer skepticism typically targets rigor, not the purpose of qualitative inquiry: Was sampling defensible? Are the codes reproducible? Is reflexivity explicit? Can another team follow the analytic audit trail? Even sympathetic reviewers may default to “insufficient detail” when methods are not reported with checklist-level clarity. Editorial perspectives further point to uneven familiarity with qualitative traditions, tight word limits, and limited methodological expertise on some panels—factors that yield inconsistent assessments.1,2

What the evidence shows

Three empirical patterns explain much of the skepticism, and show exactly where to improve:

Reporting quality has often been suboptimal.

A scientometric assessment of qualitative manuscripts rated 95% of reports as moderate (57%) or poor (38%) by COREQ criteria, indicating that incomplete reporting, not the method itself, drives many concerns. Journal endorsement of guidelines correlated with better reporting.3Checklist uptake improved quality but remains modest overall.

A large meta-review (1,695 reviews; 49,281 studies) found reporting quality improved after COREQ’s introduction, yet average total scores rose only from 15.5 to 17.7 (of 32), reflecting lingering gaps in reflexivity, analysis, and reporting detail.4Many papers omit basic standards entirely.

In one health-professions education corpus, only ~21% (28/134) referenced SRQR or COREQ, suggesting many submissions still lack a shared language for rigor.5

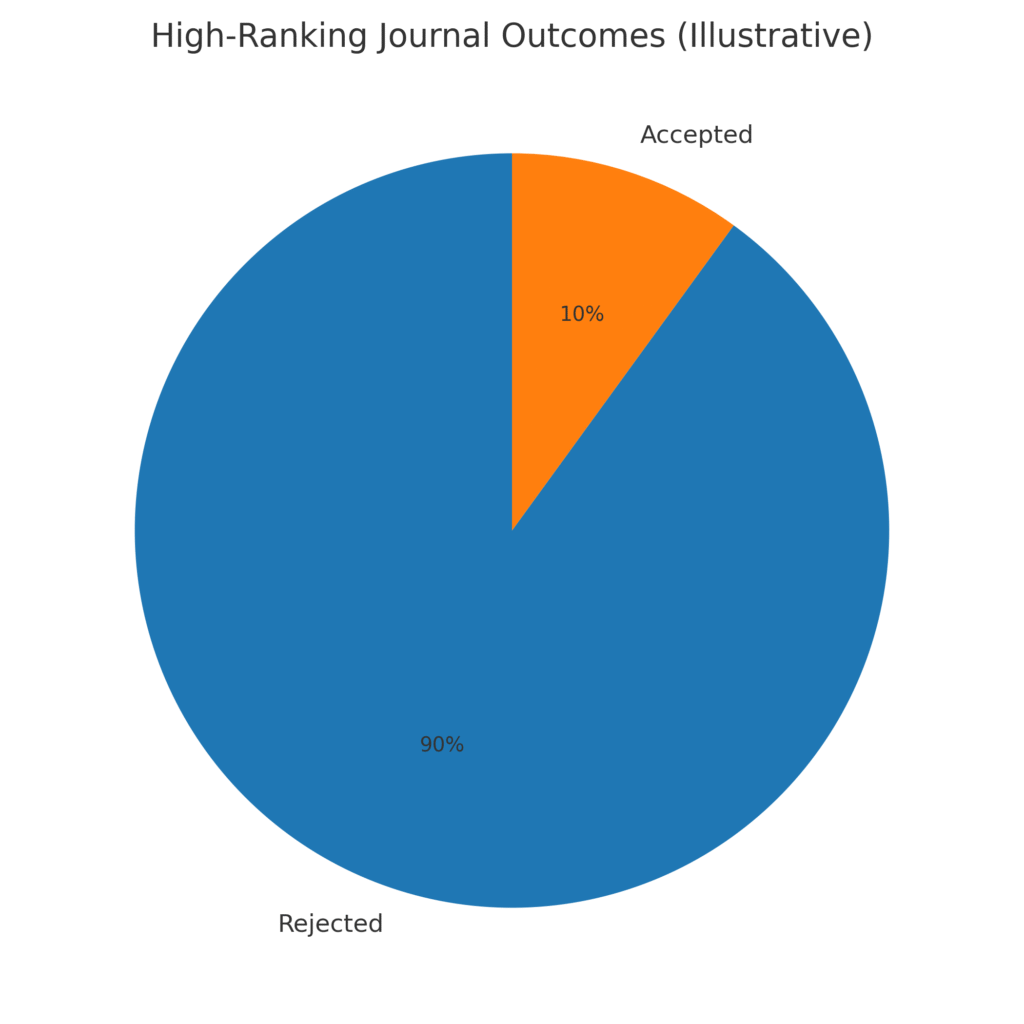

Layer on the reality that top-tier journals reject the overwhelming majority of submissions (across methods); in such scarce environments, any ambiguity becomes disqualifying.6

Where qualitative rigor most often breaks down (and how to fix it)

1) Reflexivity & positionality

Breakdown: Minimal disclosure of researcher roles, assumptions, or analytic standpoint.

Fix: Provide a concise reflexivity paragraph: researcher background, relationship to participants, power dynamics, and how these were managed (e.g., bracketing, memoing, peer debrief). Align to COREQ/SRQR items. 1,2

2) Sampling logic & saturation/sufficiency

Breakdown: Vague rationale for sample size; “saturation” asserted rather than demonstrated.

Fix: State strategy (purposive/maximum variation/theoretical), stopping rule, and evidence for sufficiency (e.g., code-stability analysis across interviews).

3) Codebook transparency

Breakdown: Codes named but not defined; unclear inclusion/exclusion rules.

Fix: Share a codebook with labels, definitions, decision rules, and exemplar quotations (appendix or repository).

4) Reliability and adjudication

Breakdown: Solo coding with no cross-checks; or “we reached consensus” without a process.

Fix: Use independent dual coding on a pilot set; compute intercoder reliability (e.g., Cohen κ, Krippendorff α, Gwet AC1), hold discrepancy meetings, refine rules, document adjudication, and report the final values.

5) Analytic chain of evidence

Breakdown: Jumps from quotes to themes with no intermediate logic.

Fix: Maintain an audit trail (memos, decisions, versioned codebook) and show matrices (case×code; theme×evidence) or thematic maps that trace data → codes → categories → themes.

6) Over-reliance on AI/auto-coding

Breakdown: Automated clustering presented as analysis.

Fix: Treat AI as a screening aid only; all analytic claims flow from human coding and adjudication, with AI outputs treated as prompts to be confirmed or rejected.

Why more than one coder matters (and when it doesn’t)

Multiple coders do not make a study “quantitative”; they make it credible. Independent coding exposes confirmatory bias, enforces decision rules, and surfaces negative cases. Use dual coding at least for a calibration subset; then, if resources are constrained, scale to single-coder with periodic reliability checks. Report the metric, thresholds, and how disputes were resolved—that’s what reviewers look for. (COREQ and SRQR expect transparency on team roles, analysis steps, and checks.)1,2

A reviewer-friendly template

Design & stance: Qualitative approach (e.g., IPA, grounded theory, thematic), epistemological stance, and why it fits the question.

Sampling: Strategy, inclusion/exclusion, recruitment, size rationale, and saturation/sufficiency evidence.

Data collection: Guides/prompts, pilot testing, interviewer training/backgrounds.

Analysis: Coding phases; who coded what; IRR metric & values; adjudication; memoing; software.

Trustworthiness: Triangulation, member checking (as appropriate), peer debrief, negative-case analysis.

Reflexivity: Positionality statement; plausible influences; safeguards used.

Evidence chain: Thematic map/matrix; exemplar quotes and counter-quotes.

Ethics & data: Approvals, de-identification, secure storage, data-sharing plan.

How our service addresses reviewer skepticism

ProData Analytics pairs experienced academicians (former PIs, study-section members, journal reviewers) with methodologists/statisticians to deliver end-to-end rigor:

Checklist-aligned reporting (COREQ/SRQR) so reviewers don’t have to infer your methods.^1,2^

Dual-coder workflows + IRR (κ/α/AC1) with documented adjudication and a refined codebook.

Audit trails & memoing that make the analytic chain reproducible.

Reflexivity coaching that surfaces and manages author bias rather than hiding it.

CAQDAS proficiency (NVivo, ATLAS.ti, MAXQDA, Dedoose, QDA Miner/WordStat, Quirkos, Taguette), with deliverables in your tool of choice.

Publication-ready outputs (Methods/Results, matrices, thematic maps, quote tables) formatted for target journals.

Result: Your manuscript speaks the language of rigor reviewers recognize, reducing “nice idea, unclear methods” rejections and positioning your work for high-rank outlets and funder confidence.

The take-home for skeptical reviewers

The best antidote to bias is transparency. The literature shows that when authors meet explicit reporting standards and document reliability and reflexivity, reviewer confidence rises; where studies fall short, it is usually because details are missing, not because qualitative inquiry is inherently weak. Improving the signal of rigor is entirely within an author’s control.3–5

Sources

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

Walsh S. Adherence to COREQ reporting guidelines for qualitative research: a scientometric assessment. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2020; 19 :https://doi.org/10.1177/160940692098214

de Jong Y. Meta-review of COREQ/ENTREQ reporting completeness in qualitative studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021;21:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01363-1

Foster J. Utilization of qualitative methodologies and reporting checklists (SRQR/COREQ) in health-professions education. JID Innov. 2022;18;3(2):100172. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2022.100172

Frankel RM. An editor’s perspective on publishing qualitative research: challenges in peer review and space constraints.J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39(2):301-305. doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08361-7.

EQUATOR Network. COREQ: Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research. Available at: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/coreq/ Accessed August 14, 2025.

EQUATOR Network. SRQR: Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Available at: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/srqr/ Accessed August 14, 2025.